—

Health Policy Basic Frameworks 2014-2016

Wednesday, 26. March 2014, 18:46 — HPI

Modernization of Slovak hospitals

New publication of series “Health Policy Basic Frameworks“. In this publication, in addition to macro prognosis of resources for health for the period 2014-2016, we are focusing on hospitals and the need for their modernization. The authors quantify the investment gap, looking for the resources to cover it, bring examples of modernization of hospitals abroad. A separate chapter is dedicated to the payment mechanism, as well as human resources in healthcare.

New publication of series “Health Policy Basic Frameworks“. In this publication, in addition to macro prognosis of resources for health for the period 2014-2016, we are focusing on hospitals and the need for their modernization. The authors quantify the investment gap, looking for the resources to cover it, bring examples of modernization of hospitals abroad. A separate chapter is dedicated to the payment mechanism, as well as human resources in healthcare.

Authors: P. Pažitný, T. Szalay, A. Szalayová, K. Morvay, R. Mužik, M. Pourová, D. Kandilaki, P. Balík, T. Sivák

Published by the Health Policy Institute, March 2014, 128 pages, ISBN 9788097119386

Free to download (pdf) – in Slovak language

Executive summary

WHAT WILL YOU FIND IN THIS PUBLICATION?

The current issue of our traditional publication “Basic Frameworks”, this time for the years 2014 – 2016, is focused on the most pungent segment of Slovak health system – hospitals. First of all the initial chapter 1 defines basic macroeconomic framework for the years 2014 – 2016 and the Chapter 2, on the basis of these frameworks, is devoted to perspective of revenues and expenditures in the health sector.

Chapter 3 provides a brief overview of the organization and management of hospitals and subsequently it introduces three ways we calculate the investment gap of Slovak Healthcare system and Slovak hospitals. Chapter 4 shows us how other countries solved the problem of recapitalization and modernization of hospitals. At the end of each subchapter there is a brief lesson for Slovakia coming from the foreign examples.

Chapter 5 summarizes available options of financing Investment gap, and suggests realistic sources of modernization in the short but also in the long term. Chapter 6 is dedicated to hospitals payment mechanism in Slovakia and shows successful foreign examples and summarizes the current state of DRG implementation in Slovakia.

Chapter 7 is devoted to human resources as the third key pillar of hospital modernization (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Three pillars of hospital modernization

Source: authors

WHY ECONOMIC GROWTH CANNOT BE FULLY TRANSMITTED TO CREATION OF HEALTH INSURANCE PUBLIC FUNDS?

Gradual acceleration of economic growth can be expected since 2014 again. From 2014 to 2016, we expect the pace of economic growth in the range from 2.3 to 3.6%. To ensure that the full economic growth is projected to growth of health resources, prevent those remaining limiting factors:

- Low wage rate (only 38%). Slovakia with wage quota of about 0.38 has significantly lower share of wages in GDP than other matured economies. Values of wage quotas are placed in the interval from 0.42 to 0.59 for most countries, meaning that 42% to 59% of the gross value added is the compensation of employees. Nevertheless health insurance system was (and is) dependent mainly on the amount of wages.

- High threshold of employment growth (to 4.2% of GDP). It is a critical value of real gross value added, above which increases the employment. For employment to grow in Slovakia it had to achieve an average growth of real gross value added of 4.2%, while for other countries was sufficient growth at 0.9% (Germany) and 1.2% (Austria).

WHAT MACROECONOMIC FRAMEWORK CAN WE EXPECT INBETWEEN 2014 – 2016?

In 2013 the inflation rate will be probably significantly lower than in previous year. The reason for this is the lack of alterations in regulated prices or indirect taxes, as well as relatively weak internal demand. In following years the inflation rate can slightly increase. It will be the weak domestic demand and government unwillingness to permit changes in regulated energies prices which will have an affect against its steeper increase.

Indicators of the labor market are those, which have the biggest impact on the healthcare system incomes (through contributions). The weak economic growth cannot generate new extensive employment without the help of any special instruments. In the second and third quarter of 2013 came to slight decrease of the employment (8 thousands people in the third quarter). In the years of 2014 till 2016 we can expect slight increase in the number of labor force.

It is probable that the unemployment rate may slightly decrease in 2014. Although it is interesting that thanks to the “correction” of the older employment data actual evolution doesn’t look so unfavorable as was expected before (Slovak statistical office made a change in methodology and therefore decreased the number of employed labor of more than 30 thousands people in 2013 and there made a drop of default base).

Table 1: Selected macroeconomic parameters

f – forecast

Source: Real data of Slovak statistical office, HPI prognosis

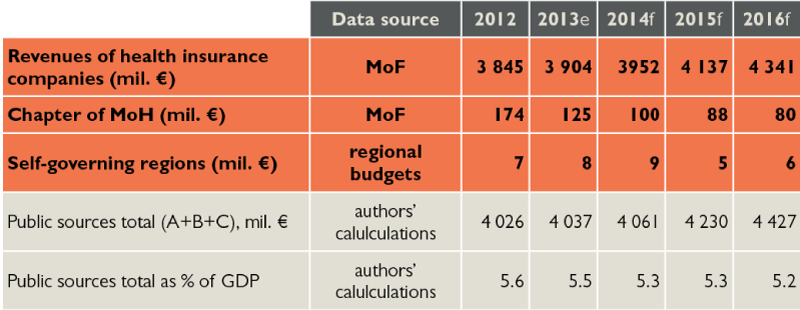

WHAT WILL BE THE REVENUES AND EXPENDITURES IN HEALTHCARE?

Economic growth is only weakly tied to improving the performance of the labor market and the income on which depends formation of resources in health care. Such a change takes place in revenue structure, which weakens the dynamics of resource of health insurance companies. Wages, which were previously substantial basis for premium payments are less weighted in the structure of earnings.

Share of public health resources (% of the GDP) in the medium term is likely to decline from 5.6% to 5.2% of GDP. Even if there is a revival of the economy, the labor market (and hence contributions!) Reacts with a lag.

Public funds could rise by 2016 to a total of around 4,375 mil. Euros (from around 4026 mil. euros in 2012).

In the same period, the private funds (in the broadest understanding) could get to the level of 2,570 mil. Euros (from an estimated 2,240 mil. Euros in 2012). This means higher dynamics of private funds rather than public.

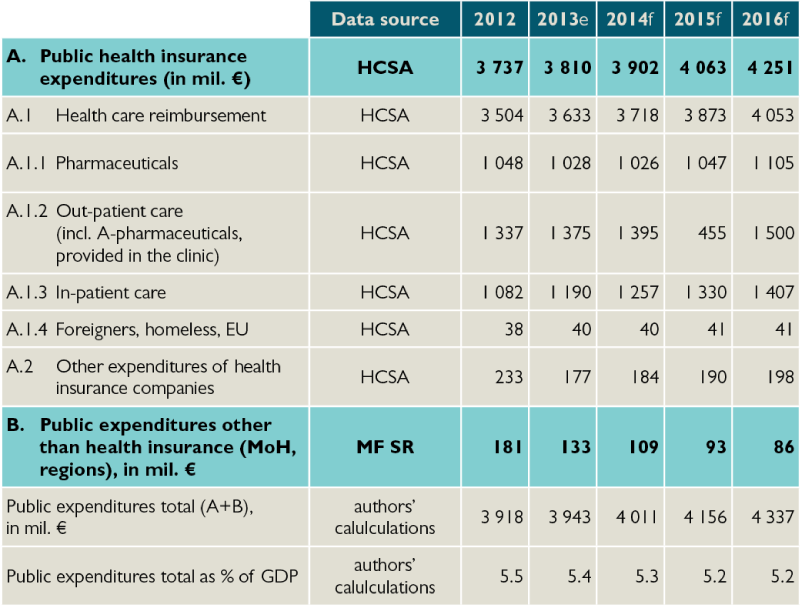

“Winners” in the distribution of health expenditures will probably be hospitals (mainly at the expense of drugs expenditures). VšZP continues to push prices upwards.

Table 2: Public resources in healthcare

e – estimate, f – forecast

Source: reality according to Ministry of Finance and VÚC budgets, prognosis according to HPI, Ministry of Finance and VÚC budgets

Table 3: Public expenditures on healthcare

e – estimate, f – forecast

Source: reality according to Ministry of Finance and VÚC budgets, prognosis according to HPI, Ministry of Finance and VÚC budgets

WHAT IS THE AVERAGE SLOVAK HOSPITAL?

Slovak hospitals are mostly non-profit and contributory organizations. Also they are undercapitalized and at a loss, and if they are state owned (about one quarter) then they are usually every three years debt forgiven.

A typical general hospital in Slovakia is more than 40 years old, owns an estate with 30 buildings scattered around on it.

WHAT IS THE INVESTMENT GAP IN SLOVAK HEALTHCARE SYSTEM AND HOSPITALS?

The estimated “gap” in comparison with the Czech capital formation reached 137 million euros a year, in comparison with Austria it is up to 441 million euros per year. In term of 20 years it represents at least 2.74 billion euros.

Investment needs according to MZ SR reaches up to 197 million euros per year. In term of 20 years, it is 3.94 billion euros.

According to alternative HPI calculation investment needs is at its minimum at 134 million euros per year and a maximum of 401 million euros year. In term of 20 years it is 2.68 billion euros to 8.02 billion euros.

WHAT IS THE LESSONS OF SELECTED FOREIGN EXAMPLES?

United Kingdom. Despite the fact that it is a tax model with one “insurance company”, since the days of Margaret Thatcher strong market forces enforce in healthcare. The first of this was “GP fundholding”, followed by NHS trusts and hospital trusts. Involving the private sector has significantly stepped up after 1997 and therefore we will be particularly interested in the story called public-private partnerships, through which Great Britain modernized large percentage of hospitals (for about € 123 billion).

Czech Republic. Historically invested in hospitals significantly more than Slovakia. At present, the main burden of capital expenditure lies on regions. Public-private partnerships have not been very successful, it could be an inspiration for Slovakia what errors in such projects avoid in our latitudes.

Poland. The reform aims at restructuring hospitals, to open the hospital sector to private ownership and to establish large hospitals specializing in several areas of treatment as well as specialized hospitals in areas that were monopolized by state hospitals.

Transformation of hospitals is still a real solution to debt situation of hospitals in a country undergoing a transformation of health care system much like in Slovakia. Transformation in Poland does not mean that the hospital will be privatized. Through responsible financial policy hospital management has the opportunity to save the hospital from bankruptcy and avoid privatization by private entities.

Portugal. No need to worry about the elements of business environment in healthcare. Competence in managing need not only have the Ministry of Health, but the Ministry of Finance may also be an equal partner, which has a better capacity concerning issues in budgeting and financial transactions. Rules of corporate governance, such as in the form of a board (administrative, supervisory), where members are competent hospital staff can lead to increase transparency and accountability. Management (loss as well) remains in hospital whilst inefficient management leads to bankruptcy, which can be solved by increasing capital or through certain subsidies. Hospital financing through public-private partnership is administratively difficult process and improper adjustment of cooperation can lead to a lack of state control.

Spain. One possibility is the construction of a new hospital via specific model of public private partnership – concession model. The partner of the state may not be exclusively one company, but for example, a consortium composed of private insurance companies or construction companies. Separation of primary and secondary healthcare is not appropriate, therefore a coordinated model should be selected – an integrated system that encompasses the administration and management of both types of care.

Germany. After 1989 the situation in eastern Germany was similar to that in the former Czechoslovakia. Unlike us in Germany, there was massive capital investment in hospital equipment to operate close to West German medical facilities standards. Hospitals are – much like in Slovakia – mostly owned by counties, districts, or cities whose funding and effective management goes beyond the ability of local governments. This situation is dealt with either partial or complete privatization, which enables commencement and development of private hospital networks in Germany. An example of privatization is faculty hospital in Hamburg, this shows that even a large hospital privatization project of significant importance for a large number of people can be successful and can bring positive results in the quality of health care as well as a relief of public finances. From the regulatory point of view there is an interesting attempt to introduce investment lump sum performance-oriented payments linked to DRG.

Sweden. Recent developments in Sweden points to a bright new trend in the development of healthcare sector. Gradually, first through the outpatient sector and also through the inpatient sector it is coming to release of legislation and to entry market elements and private equity. St. Göran is a state hospital belonging to district, which operates private equity group Capio, it is also an inspiration not only because of its untraditional arrangement, but also that regularly moves the standards of quality in the hospital sector in Sweden.

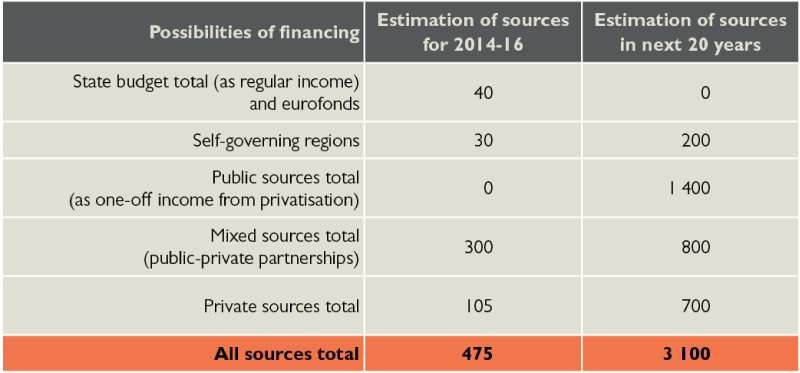

WHAT ARE THE REAL POSSIBILITIES IN HOSPITAL CAPITAL INVESTMENTS?

In short term (2014 to 2016) we estimate potential resources for modernization of hospitals in structure:

- € 300 million of public-private partnerships

- € 105 million from private sources

- € 40 million budget – only Eurofund

- € 30 million VÚC

- € 0 million – state budget. The public resources generated from one-time income (privatization) are strongly dependent on political decision of the government and therefore we estimate them to 0 €. This form of resources is more likely in long term, in a given horizon is very unlikely.

It would be sufficient to cover calculated minimum investment needs of 2.7 billion euros but again different forms of sources have a different likelihood of implementation:

- € 1.400 million from privatization is potentially the largest source of income but this source is also strongly dependent on future decisions of the government, which cannot be predicted. The amount will depend solely on the willingness of future government to privatize.

- € 800 million – the most probable form of source are again mixed resources, especially public-private partnerships.

- € 700 million – again private resources in long term horizon represent good option.

- € 200 million – VÚC

- 0 million € – State budget (including euro fond)

In our estimation would be possible to obtain around 3.1 billion euros in the long term (20 years).

Table 4: Summary options of hospitals modernization in mil. euro

Source: HPI

WHAT ARE THE ASSUMPTIONS FOR DRG IMPLEMENTATION IN THE SLOVAK REPUBLIC?

Slovakia is one of the few EU countries where DRG is not in use. Its implementation is the key instrument to fairer hospital reimbursement. Road to its implementation will not be easy.

Around the implementation of DRG is still much issues and their resolution will affect both, the quality and the success of DRG implementation. It is not clear, for example, whether the base rate will be regulated centrally by MZ SR as a fixed or will be left to the agreement between the provider and the hospital. Especially in the case state would want to regulate it, it will be important whether there will be same price for all or whether it will differ between individual hospitals. The reasons for differences in prices may be e.g., higher or lower quality of services, hospital localization, but especially at the beginning the volume of preceding resources available. As the volume of resources for hospital care will not be changed, it can be fairer allocated among different providers, the introduction of DRG payments will mean for some hospitals more revenue, but on the contrary, others will have less resources.

Sudden change could result in destruction of these hospitals, because of that this equal rate is introduced gradually so that less efficient hospitals were able to adapt to these changes. Immediate or rapid change can cause a negative reaction of related hospitals, which could occur to stop or repeal DRG implementation.

The implementation of cost calculation for individual cases in hospitals will be also a problematic phase. Currently, only very few hospitals monitor costs of individual patients. Collecting necessary data for relative weights calculation will mean a significant changes in hospitals’ accounting. Even in Germany, from where we are adapting the system, not all hospitals are involved in data collection because they do not quite fulfill all of the conditions. Out of about 2.100 German hospitals only about 250 are collecting economic data (even though mainly major hospitals which have proportionately greater share of hospitalization). Selection of similar sample of hospitals (e.g. 12% as in Germany) would be in our view a small number and therefore was not representative. For our calculation of relative weights, we will need to collect data from almost all hospitals. Even for this reason, it is planned to adopt the German relative weights first. At the time of real DRG payment mechanism implementation the local relative weights would be used. The German weights differ from ours, whereas the ratio between the intensity of the different types of resources is different between us and Germany (e.g. salaries of health workers are significantly different, but the prices for medical supplies not).

Parallel reporting in DRG – besides the present one, which is a subject of insurance companies payment – serve in the first year for data collection which is needed to calibrate the DRG. Based on the analysis of these data will probably be politically decided whether the DRG implementation project will continue or not.

Start of DRG as a payment mechanism is scheduled for 2016. Year 2016 is also an election year. Change in funding in pre-election period is unlikely (due to the risk of unnecessary change of status quo, which could negatively affect the electoral preferences).

In after-election period they will run re-evaluation of DRG again whether to start it or purposefully modify.

IS DRG A STANDARD IN HOSPITALS’ PAYMENT?

Operating costs of hospitals are in most countries paid by some form of DRG. For Slovakia it is crucial to monitor development in Germany, as under a contract between ÚDZS and INEK, Slovakia takes the German DRG model, called G-DRG.

Table 5: Overview of payment mechanisms

| Country | Name | No. of groups | Basic rate/prices |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | G-DRG(combined with a global budget for hospital) |

1.200 |

First individual, then united at the level of 16 federal states with a view to unify at the level over whole Germany (2015) |

| Netherlands | DBC(combined with macro budget of all hospitals) |

4.400 |

DBC are divided into two groups – list A and B.Prices on list A are centrally regulated and mostly under the prior system reform reimbursement.

Prices listed on B list are negotiated individually between insurers and providers |

| UK | HRG |

1.400 |

The payment amount is determined based on the average hospital cost and includes the cost of personnel, equipment and capital expenditures.It is specified the year ahead, by the Ministry of Health according to standard methodology based on average costs obtained from all hospitals. This price is the same for all providers, regardless of geographic location. However, since hospitals bear some of the costs that are beyond their control and that they cannot alter nor by higher efficiency, the Ministry of Health pays additional payments to providers based on index of “market forces factor” that takes into account the cost of staff, location and building. |

| Poland | JGP |

518 |

In Poland there are 518 JGP groups in total, each of them graded from 5 points (less serious surgery) up to 4706 points (complicated procedures such as cell transplantation). Each hospital can obtain certain amount of points from JGP groups based on its performance and thus obtain adequate resources from the National Health Fund (each hospital the same amount for one point). |

| Czech Republic | DRG(combined with individually agreed contracts and centered care) |

1.036 |

To the calculation enters so called technical (national) base rate, which is set at CZK 29.500 in the Reimbursement agreement for 2013, and so called individual base rate.Individual base rate reflects the historical development of reimbursement of hospital care in the calculation and depends on long-term behavior of individual hospitals.

Technical rate has a weight of 30%, and individual rate has a weight of 70%. |

HOW TO BUILD A HUMAN CAPITAL?

The success of the modern hospital will not depend only on buildings and technologies, but on the management as well, organization of work, corporate culture and professionalism of the employees as well – on health professionals. How is Slovakia doing with human resources in healthcare and what are the future perspectives?

Imminently we are facing a challenge of workforce migration abroad. Opening of the labor market in the EU resulted in hospitals outage of one generation of doctors.

Wage assessment plays when deciding about leaving an important role, but equally important factors are space for self-fulfillment, working atmosphere and corporate culture Those will not replace central wage regulation, which, in turn, even out any differences in quality and amount of work done, which deepens disincentives of better and diligent.

No. of hospital beds over one nurse in Slovakia has not changed over the last decade (2.1), however, there has been a significant change in doctors situation. After massive departures at start of millennium the number of hospital doctors has passed to its minimum in 2005. Since then rose up by over 21%.

While the proportion of young doctors retains, share of generation of forties decreased by one third.

Characteristic trend is the feminization of Slovak healthcare. Over the past 15 years the proportion of women studying medicine has increased from 60% to 70%. Average proportion of female doctors in OECD countries is 44%.

Despite the fact that migration of health professionals presents important health/political topic throughout Europe we do not have enough relevant information about it. WHO (2009) notes that most countries do not have reliable and/or sufficient data about the health professionals, they do not collect information on migration flows and vary in definitions.

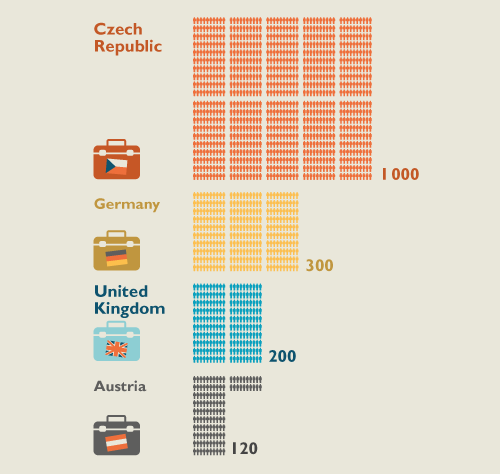

One useful proxy indicators of the estimation of migration flows, according to WHO is the number of applications for recognition of education equivalence at the concerned institution. Ministry of Health published an estimate of the final destination of outgoing Slovak doctors (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Estimated number of Slovak doctors abroad – frequent working destinations

Source: Ministry of Health estimation, 2013

Factors which expel health worker from the country (PUSH factors) are compared to the attraction of work in another country (PULL factors). Usually referred to in complementary pairs (Table 6).

Table 6: Main push and pull factors of health workers migration

|

PUSH factors |

↔ |

PULL factors |

|---|---|---|

|

Low wage (absolute and / or relative) |

↔ |

Higher wagesPossibility of remittances |

|

Poor working conditions |

↔ |

Better working conditions |

|

Lack of resources for more effective work |

↔ |

Healthcare with better resources |

|

Limited career opportunities |

↔ |

Career opportunities |

|

The impact of HIV / AIDS |

↔ |

Political stability |

|

Unstable/unsafe work environment |

↔ |

Travel options |

|

Economic instability |

↔ |

Help |

Source: Buchan et al. (2003)

Other important PULL factor is the language, geographical proximity and the existence of compatriot’s community in target country.

To reach a balance while maintaining open labor market it is necessary:

- To ease the entry of doctors to Slovakia

Along with relatively low language barrier Ukraine represents significant potential for getting cheap and skilled labor. Its arrival would also allow significantly reduce the pressure for further wage increases. Slovakia may (as an immediate neighbor of Ukraine) from its position to benefit and contribute to Ukrainian to adaption to Europe. In the case, the convergence between the EU and Ukraine will not continue, it is desirable to find ways to simplify arrivals of local health workers to Slovakia.

- to increase the number of graduates in medicine

The number of candidates and the number of graduates grows, additional increases may stumble upon the capacity of universities. In parallel with Slovak students foreign students (private payer) study medicine a well. Among the enrolled students they make a third.

- to increase a retention of doctors

Some countries (e.g. Hungary) introduced for graduates of public service obligations – either a cost of their studies are worked in domestic healthcare, or the tuition is re-paid at fair amount.

To improve the ratio of push and pull factors can be achieved by changes in the following areas:

- remuneration

central wage regulation leads to remuneration leveling, suppresses differences in performance and subsequently suppresses employee motivation, remuneration on the basis of quality and productivity allows quality physician to obtain sufficient income to not to consider an immigration;

- self-realization

supporting the physician’s professional development aligned with the intentions of hospital development is mutually beneficial and leads i.a. to greater loyalty to the employer;

- social appreciation

promotion of bearers in healthcare;

- working conditions

workplace relations, the availability of technology, work organization, management, corporate culture requires an honest interest of the owner and its consistency over time;

- education

in addition to supporting professional development doctors need to acquire knowledge on areas that are not a subject to study in medical schools (Health Economics), for better understanding of the objectives of the organization and to manage to constructively contribute to its development;

- to motivate Slovaks abroad to return

Specified retention conditions must be met first for the return. Physicians who would return to Slovakia would bring in addition a knowledge, experience and contacts and other corporate culture. The arrival of these people into leaders’ positions may significantly contribute to their modernization in Slovak hospitals. It could be a factor for retention of other health professionals. It is therefore convenient to consider active recruiting and create a condensation nuclei of modern health care in Slovakia around these doctors.

- reduce the need for doctors

Transfer of the job description and responsibilities to other nonmedical staff and the patient himself, change in organizing and planning…

In the midterm horizon the challenges are of the consequences of demographic aging: increase in the number of people requiring some form of institutional and non-institutional care (chronic disease, long-term care, mental health, nursing, caring).

The method and form of delivery of health – and social – care will be in following years fundamentally changed. They will be more or less flexible to adaption to the needs of clients. Providers will seek innovative solutions. Stronger pressure to definitions adaptation, status, competence of health workers and their education.

About the success of providers will decide a patient-consumer eventually, it depends on the innovators in the Slovak healthcare, if they convince him.

News

The amendment of the Decree on emergency medical service

Health insurance companies returned over 400 thousand €

The HCSA received 1,647 complaints last year

A half million people will earn more

Most of public limited companies ended in the black

Debt of hospitals on premiums has grown to nearly € 105 MM

Slovak health care may miss € 250 million next year

Profits of HIC amounted to € 69 mil. last year

Owners of Dôvera paid out money but did not paid taxes

Like us on Facebook!

Our analyses

- 10 Years of Health Care Reform

- New University Hospital in Bratislava

- Understanding informal patient payments in Kosovo’s healthcare system

- Analysis of waiting times 2013

- Health Policy Basic Frameworks 2014-2016

- Analysis of informal payments in the health sector in Slovakia

- Serbia: Brief health system review

developed by enscope, s.r.o.