—

Serbia: Brief health system review

Tuesday, 28. January 2014, 15:02 — Roman Mužik and Slavica Karajičić

Brief review of the health system in Serbia provides informations on organization and provision of services, financing, resources or corruption in health care system of Serbia.

Abstract

Republic of Serbia, a parliamentary democracy country, is located at the crossroads of Central and South-eastern Europe. Serbia has population of 7.120 million. Serbs represent 83.32% of the population; Hungarians are the second largest ethnic group (3.53%), followed by Roma 2.05% and Bosniaks 1.81%. Serbia is an upper-middle income economy with the service sector dominating country’s economy, followed by the industrial sector and agriculture. The economy had an unfavourable trade deficit of -1.7% and GDP per capita was 4.144 euro in 2012. Health care system is a Bismarck model with social insurance based on universal health coverage from the National Health Insurance Fund. Private health insurance exists in supplementary form (covers faster access and enhanced consumer choice). Financing of hospitals in Serbia is based on DRG system while primary health care is based on capitation. Health care of the population is directly provided through a network of health care institutions and divided to three levels: primary, secondary and tertiary health care. It is possible to distinguish levels of corruption in health care in Serbia which are strongly interconnected: macro, mezzo and micro level. Serbia has 3.9 (out of 10) Corruption Perception Index (CPI), so CPI puts Serbia on 80th place out of 176 countries.

Introduction

|

Total land area: 87,460 km² |

| (Source: The World Bank, Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia-census 2011) | |

Republic of Serbia is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, covering the southern part of the Pannonian Plain and the central Balkans. Serbia´s borders with Hungary from the north, Romania and Bulgaria from the east, Macedonia from the south and Croatia, Bosnia and Montenegro from the west. It also borders with Albania through the disputed territory of Kosovo. Belgrade, the capital of Serbia, is among Europe’s oldest cities and one of the largest in Southeastern Europe.

If we take a look in the historical past of Serbia, we can easily notice that during only one century Serbia changed many forms of the governing – from the monarchy to the democratic republic. Serbia is one of these post-communistic countries which have passed through the period of dramatic changes during last more than two decades. The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRJ) broke up in 1991/1992 in a series of wars following the independence declarations of Slovenia and Croatia in 1991, and Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992. Macedonia left the federation peacefully in 1991. Yugoslavia as a community of South Slavic people existed in various formations until 2006 when Montenegro declared its independence. In 2008 the parliament of UNMIK-administered Kosovo declared independence, with mixed responses from the international community.

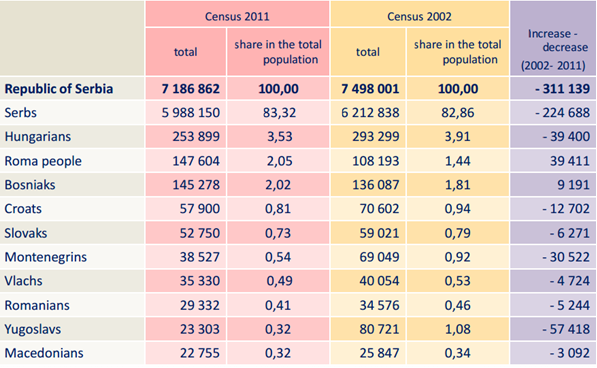

Serbia is a unitary state composed of 5 regions including two autonomous provinces, Vojvodina and Kosovo, many districts and municipalities/cities. The Republic of Serbia is a parliamentary democracy with a population of 7.120 million, according to the recent Census in 2011. Serbs represent 83.32% of the population, Hungarians are the second largest ethnic group (3.53%), followed by Roma 2.05% and Bosniaks 1.81% (see Table 1).

Table 1: Republic of Serbia – the most predominant ethnic communities in 2002 and 2011

Source: 2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia, http://media.popis2011.stat.rs/2012/Presentation_Ethnicity.pdf

As the main the reason of a decreasing population is a trend of negative population growth and emigration abroad as well as boycott of the census in three municipalities in the south of Serbia. Serbia officially applied for European Union membership in December 22, 2009. Serbian previous and current reform oriented government led by Nationalist Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) is working on harmonization national law framework with the EU standards and requirements as well as finding a political solution for Kosovar and Serbian populations living in that region.

Economy and global indicators

Serbia is an upper-middle income economy, according to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, with the service sector dominating country’s economy, followed by the industrial sector and agriculture. Its currency is Serbian Dinar. One Euro has value around 114 dinars. Dinar depreciated remarkably since 1993 and that’s why many investors still do not see Serbia as a great place for their investments.

The economy has an unfavourable trade deficit. According to World Bank data, real gross domestic product (GDP) growth was in 2012 negative 1.7 %. GDP per capita (PPP, international dollar) in 2012 was 10,772. Thus, total unemployment rate (15-64 years) in 2012 was enormous 26.1% (Serbian Statistical Office 2012), while youth unemployment rate in the same year was 50.9% (National action plan of employment 2012)

Since 90’s until nowadays, Serbia has been coping with the socio-economic and political problems due to rapidly changing political and economic environment and that is has remained a serious challenge. Most of the former socially-owned companies are privatized and social welfare programs are restricted. Such a situation produced more people living in poverty. According to official statistics, 9.2% of people live in poverty, which particularly affects jobless people, children, single mothers, refugees, internally displaced persons and ethnic minorities, mainly Roma population (UNDP, 2012). One out of ten citizens in Serbia was living with less than 8.544 dinars per month in 2011 (approx. 70-75 euro). In the same time, economic (not only) structures are prone to corruption due to the lack of regulatory authorities and control mechanisms.

Health care

Health status

The population of Serbia is suffering mostly from chronic non-communicable diseases. The leading causes of death in Serbia are almost identical to the ones in the developed parts of the world. Serbia made the biggest health progress in life expectancy and infant mortality. Maternal mortality, although rare, showed variations over years, primarily due to differences in coding of causes of death.

Infant mortality in Serbia is declining steadily (from 14.4 ‰ in 1991 to 11.0 ‰ in 2000 and 7.0 ‰ in 2010). Life expectancy at birth in Serbia has prolonged with an average of 74.6 years. Life expectancy is 71.9 for male and 77.2 for women. Estimated infant mortality and probability of dying before the age of 5 for Roma living in urban slums in 2006 was 3 times the national average. In addition, tuberculosis fell from 37 per 100,000 people to 24 per 100,000 people between 2003 and 2008 (WHO, 2012). The Table 2 shows some statistics on population growth rate, birth rates, fertility and mortality rates.

Table 2. Statistical data on population in Serbia

|

Life expectancy at birth, total |

Life expectancy at birth (female) |

Life expectancy at birth (male) |

Population growth rate % |

Birth rate per 1.000 population |

Total fertility rate children born per woman |

Infant mortality rate per 1000 live birth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

74.6 |

77.2 |

71.9 |

-0.47 |

9.4 |

1.4 |

6.3 |

Source: Institute of Public Health of Serbia Health, 2011; Serbian Statistical Office 2011

The most common causes of reporting to a general practitioner in the Health Centre are respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Also, there is an increase in the number of patients with neurological diseases and substance abuse (which represent a major health and socio-economic problem). In addition, tuberculosis fell from 37 per 100 000 people to 24 per 100 000 people between 2003 and 2008 (WHO, 2012).

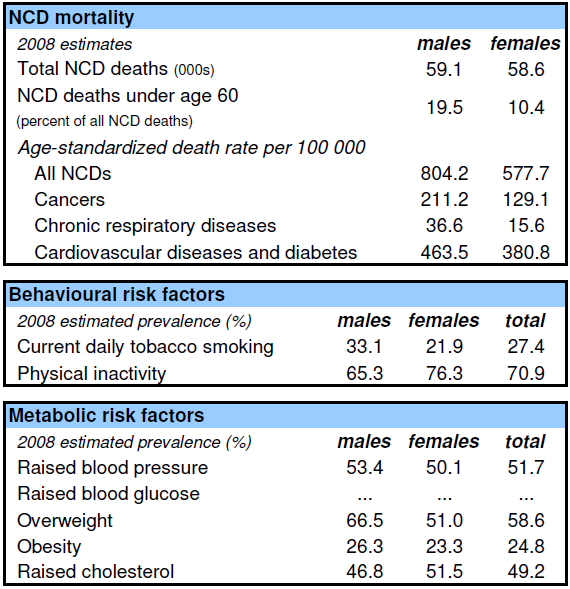

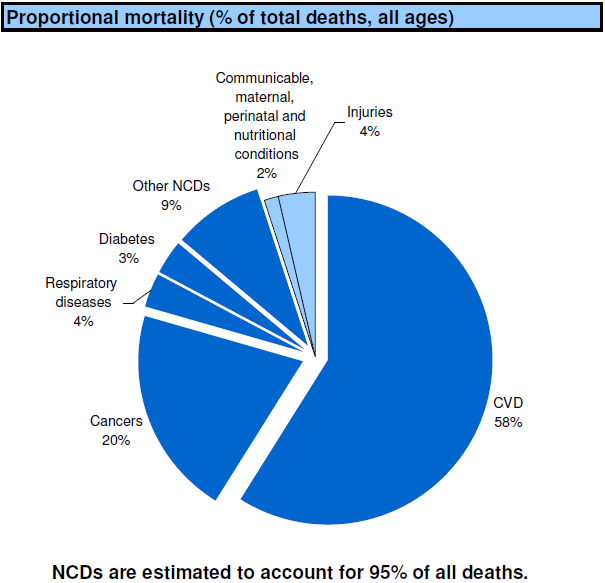

The highest burden of disease in Serbia is due to non-communicable diseases (NCD): cardiovascular disease, responsible for 55% of mortality; and cancer, responsible for 20% (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1. Mortality a risk factors of Serbia

Source: WHO HFA database at http://data.euro.who.int

Figure 2. Proporcional mortality of Serbia

Source: WHO HFA database at http://data.euro.who.int

The ageing population and high burden of NCD mortality resulted in a continuously increasing crude death rate, which reached 13.97% in 2008. The high burden of NCD is directly related to a high prevalence of risk-factors such as tobacco smoking (33% of adult population over 20 smokes) and growing obesity among adults and children. According to the national health survey 2006, 54.5% of adult population are overweight and 18% children aged 7–18 are moderately obese or obese. Only 23% of adult population reported taking daily physical activity, with 67% of adults being physically inactive. Cancer is the second biggest killer of Serbian population, responsible for more than 20 000 deaths annually. The mortality for preventable cancer is of concern, especially for cervical cancer (incidence three times higher than the EU average), breast cancer (incidence higher than the EU average) and growing lung cancer especially among women. Injuries are leading the cause of death for young people aged 15–29 (WHO, 2012).

Organization and provision of services

After the split of former Yugoslavia, Republic of Serbia, as well as other ex-Yugoslav countries, inherited Bismarck healthcare system model. Health care system in Serbia is based on universal health coverage. In Serbia, 2011, compulsory health insurance had 6,786,333 people. Insured in the health care system can be divided into two groups. First group are those citizens who have income and those have legal obligation to pay contribution (69.5% of the funds “collected” in this way). Second group are people who don‘t have income or their income is less than the established threshold, whose insurance is funded from the budget of the Republic of Serbia from the contributions of employees.

Health system in Serbia has many driving and resisting forces and some of the strongest, at a glance, are presented in the Table 3.

Table 3: Driving and Resisting Forces in Serbian Healthcare Systems

|

Driving Forces |

Resisting Forces |

|---|---|

|

1. Medical staff – well trained |

1. Corruption |

|

2. Accessibility – no matter for social status |

2. Equipment and facilities- down considerably |

|

3. International cooperation, NGO and professional associations |

3. Lack of financial resources and legislations |

|

4. General Practitioner-gate keeper |

4. Poor quality of the services and waiting lists |

Source: Author

Giving a chance to all citizens to access the health care is one of the characteristics of all post-communistic countries, regardless of social status. Poor quality of services that patients are facing is caused by lack of adequate devices and/or facilities. Serbian healthcare system (SHCS) has been severely under-funded for many years and consequently the standard of available healthcare has poor quality.

Health care for the population is directly provided through a network of health care institutions and depends on the level of organisational and operational development. In general, there are three levels of health care: primary, secondary and tertiary.

Health care at the primary level is provided by state-owned primary health centres, which cover the territory of one or more municipalities or towns. The primary health centre shall provide at least:

- preventive health care for all population categories

- urgent care

- general medicine

- health care for women and children

- health visitor service

- laboratory and other diagnostics

- prevention and treatment in dental care

- employee health care, i.e. occupational medicine

- physical medicine and rehabilitation

Primary health care in primary health centres is publicly provided by a chosen doctor who is either a medical doctor or a specialist in general medicine, or specialist in occupational medicine; specialist in paediatrics; specialist in gynaecology; and dentist (Article 98 of the Act on Health Care). General practice is a service within a primary health centre and the basic provider of health care for population over 19 years. According with the evidence, in 2011 in Serbia there were 157 primary health care centres (Table 4).

If the primary health centre is unable to provide adequate health care the general practitioner will refer the patient to the specialist and secondary health care (hospitals). Each patient can get needed treatment in one of 77 general or special hospitals in Serbia. It might be outpatient treatment (medical check-up in the clinic) or inpatient treatment.

The tertiary level of health care has the highest specialized personnel and technological equipment and provides quality diagnostic and treatment. Thus, this level cooperates closely with the secondary level by providing technical assistance and support, engage in research and activities of medical education (Clinic Research Institute, Clinical Hospital Centre, Clinical Centre).

Financing

The Health Insurance Fund (HIF) operates and oversees the health service in Serbia. The aim of the organisation is to make the health system equal for every citizen regardless of their status. The state fund covers most medical services including treatment by specialists, hospitalisation, prescriptions, pregnancy, childbirth and rehabilitation trough health centres and smaller health stations. But we have to have on mind that with 260 euro per person, Serbia is at the bottom of the European’s countries hierarchy. The main goal for the government is to increase this number in the future accordingly with EU recommendations.

Bismarck healthcare system model reflects publicly provided healthcare system financed through social healthcare insurance. National Health Insurance Fund (RZZO) of Serbia covers recurrent expenditure through input based provider payments. In 2010, majority of RZZO funding (income) originated from two major sources: 69.48% came from the employment contributions and 29.01% from the pension plan contributions (Zah, 2011). Health contribution in Serbia is 12.3 % of the salary and there are no precise data on how much of the money directly goes from the pockets of people. According to estimation, private health spending exceeds 30% (B.Radivojevic). Private health insurance exists in supplementary form (covers faster access and enhanced consumer choice).

Financing of hospitals in Serbia is based on DRG system while primary health care is based on capitation. In some special fields (such are dialysis, in vitro fertilization and hyperbaric chamber) private hospitals are hired to provide medical service to the patient based on the financial contract between hospitals as providers and the National Health Insurance Found. This is seen as a good example of involving private sector in the reduction of long waiting lists in Serbia.

Resources

According to the information from statistical yearbook of the Republic of Serbia 2012, health care services employed 161,016 people in 2011. The structure of the health personnel in 2011 is presented in Table 4.

Table 4. The structure of the health personnel in 2011

|

Physicians |

General dental practitioners |

Graduated pharmacists |

Medical workers with secondary and high education |

Medical workers with primary education |

Inhabitants per physician |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

21,079 |

2,227 |

2,133 |

58,337 |

451 |

344 |

Source: Statistical office of the Republic of Serbia, 2012

The structure of employed doctors by gender was following: 35.8% are male and 64.2% are female doctors (Institute of Public Health of Serbia Health, 2011).

Health institutions in Serbia lack minimum 450 doctors and 1,000 nurses, but it is not known how many jobs will be filled. Recently Serbian Health Minister Ms. Djukic Dejanovic announced that about 1,000 people are going to get a job in health care. The advantage will have those who are already working in institutions for a limited time. (B.Radivojevic, 2013)

Total beds in hospital institutions in Serbia in 2011 numbered 41,269, i.e. 5.7 beds per 1000 population. This number also includes day hospitals (1,473 beds), dialysis and neonatology (Institute of Public Health of Serbia, 2011). According to the same source, the number of discharged patients from inpatient institutions in Serbia in 2011 was 1,294,139, and the total number of hospital days was 10,852,202. The average length of stay per patient was 8.4 days, while the average hospital bed occupancy rate was 72%.

In the Republic of Serbia are totally 344 health care institutions. Types of Health care institutions shows Table 5.

Table 5. Health care institutions in the Republic of Serbia, 2011

|

Health Care Institutions |

Numbers of institutions |

|---|---|

|

Pharmacy |

35 |

|

Primary Health Care Centre |

157 |

|

Institute (Zavod) |

22 |

|

General Hospital |

40 |

|

Special Hospital |

37 |

|

Clinical – Hospital Centre |

4 |

|

Hospital Centre |

4 |

|

Clinic |

6 |

|

Institute |

16 |

|

Public Health Institute |

23 |

|

Total |

344 |

Source: Institute of Public Health of Serbia Health, 2011

Corruption

Recent survey in Serbia provides us with the information that 72% of the respondents as the most corrupted perceive political parties, then health and justice system. (M. K. 04.10.2013). According to the Serbia’s anticorruption agency, corruption in Serbia has removed money from budgets enough to build 500 kilometres of roads, construct 350 schools and purchase 7,500 medical devices. According to Transparency International, Serbia has 3.9 (out of 10) Corruption Perception Index (CPI), so CPI puts Serbia on 80th place out of 176 countries.

Serbian women are more likely to pay a bribe in kind – in the shape of food and drink, for example – while men are more likely to use money. Cash accounts for more than half (52%) of all bribes in Serbia and is approximately 165 euro (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2011). According to the recent research conducted in Serbia, the average bribe is 205 euro in health care sector (M.K. 2013).

Serbia was commended for its fight against organised crime and corruption in the latest report of the European Commission (EC). The new government is ready to cope with the corruption in an effective and transparent way.

Corruption in health care

It is possible to distinguish levels of corruption in health care in Serbia which are strongly interconnected: macro, mezzo and micro level.

On macro level, the corruption domains at the state regulatory role, especially during the selection of drugs to be covered from health care funds and approval is given to use new types of medical treatment in practice; in case of public procurement etc. However, particularly when those discussions are initiated by drug producers or drug importers, it is hard to distinguish whether public or only particular private interest is a matter of concern (Centre for Anti-war Action, 2005).

On mezzo level (hospital organisation and management) can happen that managers or directors are working to get a gain not for their hospital but for other parties of health care market. The following example is one of many. One hospital, where director and head of radiology department sold one device (which was old but still working) avoided all legal obligations on public purchasing. Device which costs 14,451,328 million dinars (aprox. 127,000 euro) was sold for only one million dinars (aprox, 8,700 euro) and caused the damage of approximately 120,000 euro. With the further investigation it has been discovered that that device finished in a recently opened company which owner was actually head of the radiology department. This was a great opportunity for him to obtain one public good for its own purpose (Todorovic, 2013).

On micro level are noticeable a few relations where corruption appears. First, it is evident in the relation between doctor and patient. Some research says that in 14% of cases are medical workers asking for a bribe. For example, neurosurgeon asked patient to gives between 300 and 500 euro not for himself but for obtaining “advanced” intervention which was not covered by National Health Insurance Fund in Serbia. After this case, he was arrested (Bracan, 2013). Second, it is relationship between doctor and pharmaceutical company. It is happening often that medical doctor favours one drug from one special pharmaceutical company, prescribing it more often than others. The benefits that doctor can gain is money based on the percentage of prescribed drugs or other compensation (e.g. fully covered attendance for some congress).

On all of the three levels we can notice that people who are in organisational and managerial structures are usually chosen from political party members which might not be persons with the highest expertise in a given field. Corruption among politicians is wide spread and it does affect the health system from the top to down. That is one of the reasons why health care should not be politicized.

At the end, almost every day some of Serbian newspapers are reporting about corruption in health care system and how it is wide spread among different health care systems’ players.

Why corruption in Serbia?

First reason is social-cultural. In Serbia it is kind of cultural heritage from communistic past. In that time medical doctors (especially those working in rural area) were highly respected because of their knowledge and dedication to work. People always felt to give some additional award for such a person who was helping them. It would not be money, but for sure some local and/or handmade products. That tradition kept to leave during ’90 when the situation was the worst in Serbian health care recent history. Demand for health care was so high while medical resources were limited. In these circumstances some people who had money did not ask for the price to get to treatment.

Second is economic reason. During the time of crisis, doctors were tempted to corruption. That’s why, according to WHO, Serbia failed to be on the fourth place on corruption after Tajikistan, Moldova and Morocco (S.V., 2011). Thus, Serbian economy is unstable for over 22 years. During the biggest crisis in 1993 it was difficult to find elementary medical equipment in an ambulance (gauze pads, bandage or medical alcohol) as well as to see investments in facilities, devices and/or medical personnel.

Third reason is laying in the legislation: lack of regulations, non-consistent regulations or loopholes in regulations. Led with the statement that what is not written in the law, it is allowed; people are tempted to the corruption much more than when regulations are strict and clear. This is followed with the fact that legislations do not predict very strong punishment for such persons.

Fourth, people felt scared to speak loud about their experience with corruption or they did not know how to tell it. Idea of raising public awareness has to change the picture of population and encourage people to take active participation in change of „corruption habit“, acting form the bottom to top.

In fight with the corruption, NGOs are seen as enormously important players. “Doctors Against Corruption” (founded in March 2010) consists of different profiles of public and private health professionals recognized in Health Care Sector, united in their fight against health care corruption. Thus, professional organisations can play huge role in education of medical workers on this topic and public criticism. It might be useful for the cultural change of nation, to start with the education in primary and high school by introducing relevant curriculum on these issues.

References:

- Bracan I., (19.02.2013) Vojvođanski lekari “na skeneru” zbog mita, Vecernje novosti, available from: http://www.novosti.rs/vesti/srbija.73.html:420670-Vojvodjanski-lekari-na-skeneru-zbog-mita, accessed October 22, 2013.

- Institute of Public Health of Serbia “Dr Milan Jovanovic Batut” (2011) Statistical Yearbook of Republic of Serbia, Belgrade

- International Monetary Fund http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/weoselgr.aspx, accessed October 28, 2013.

- Law on Health Care, Serbia, Official Gazette of RS 107/2005

- M. K. (04.10.2013) Kod lekara sa 205 evra mita, Novine ALO, available from: http://www.alo.rs/vesti/aktuelno/kod-lekara-sa-205-evra-mita/32849, accessed September 15, 2013

- National action plan of employment (2012)

- Radivojevic B. (07.08.2011) Bolest udara po dzepu, Vecernje novosti, available from: http://www.novosti.rs/vesti/naslovna/aktuelno.69.html:340754-Bolest-udara-po-dzepu, accessed October 16, 2013.

- Radivojevic, B. (08.05.2013) Nedostaje 450 lekara, Vecernje novosti, available from: http://www.novosti.rs/vesti/naslovna/drustvo/aktuelno.290.html:432926-Nedostaje-450-lekara, accessed October 21, 2013.

- Republicki zavod za statistiku Republike Srbije (Serbian Statistical Office) http://media.popis2011.stat.rs/2013/publikacije/domacinstva_K10_engleski.pdf, http://media.popis2011.stat.rs/2012/Presentation_Ethnicity.pdf, accessed October 18, 2013

- S.V. (30. 06. 2011.) Zdravstvo najkorumpiraniji sektor u Srbiji, Blic, available from: http://www.blic.rs/Vesti/Drustvo/263142/Zdravstvo-najkorumpiraniji-sektor-u-Srbiji, accessed October 16, 2013.

- Serbian Statistical Office, available from http://webrzs.stat.gov.rs/WebSite/

- Statistical office of the Republic of Serbia (2012), Statistical yearbook of the Republic of Serbia 2012, Belgrade, October 2012

- The World Bank, available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.TOTL.K2 and http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL , accessed October 18, 2013.

- Todorovic T., (26.06.2013)Magnetna rezonanca prodata kao otpad, Politika, available from: http://www.politika.rs/rubrike/Hronika/Magnetna-rezonanca-prodata-kao-otpad.lt.html, accessed October 22, 2013.

- UNDP, available from http://www.undp.org/content/serbia/en/home/countryinfo/, accessed October, 20 2013.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2011) Corruption in Serbia: Bribery as Experienced by the population, Vienna

- WHO available from: http://www.euro.who.int/en/data-and-evidence/databases, accessed October 20, 2013

- Zah V.(2011) The Role of Health Technology Assessment in Reimbursement Policy – Experiences from the Republic of Serbia, IME X. ÉVFOLYAM 9. SZÁM 2011. NOVEMBER

- Center for Antiwar Action, http://orgs.tigweb.org/centre-for-antiwar-action

News

The amendment of the Decree on emergency medical service

Health insurance companies returned over 400 thousand €

The HCSA received 1,647 complaints last year

A half million people will earn more

Most of public limited companies ended in the black

Debt of hospitals on premiums has grown to nearly € 105 MM

Slovak health care may miss € 250 million next year

Profits of HIC amounted to € 69 mil. last year

Owners of Dôvera paid out money but did not paid taxes

Like us on Facebook!

Our analyses

- 10 Years of Health Care Reform

- New University Hospital in Bratislava

- Understanding informal patient payments in Kosovo’s healthcare system

- Analysis of waiting times 2013

- Health Policy Basic Frameworks 2014-2016

- Analysis of informal payments in the health sector in Slovakia

- Serbia: Brief health system review

developed by enscope, s.r.o.